︎ explorer

2022

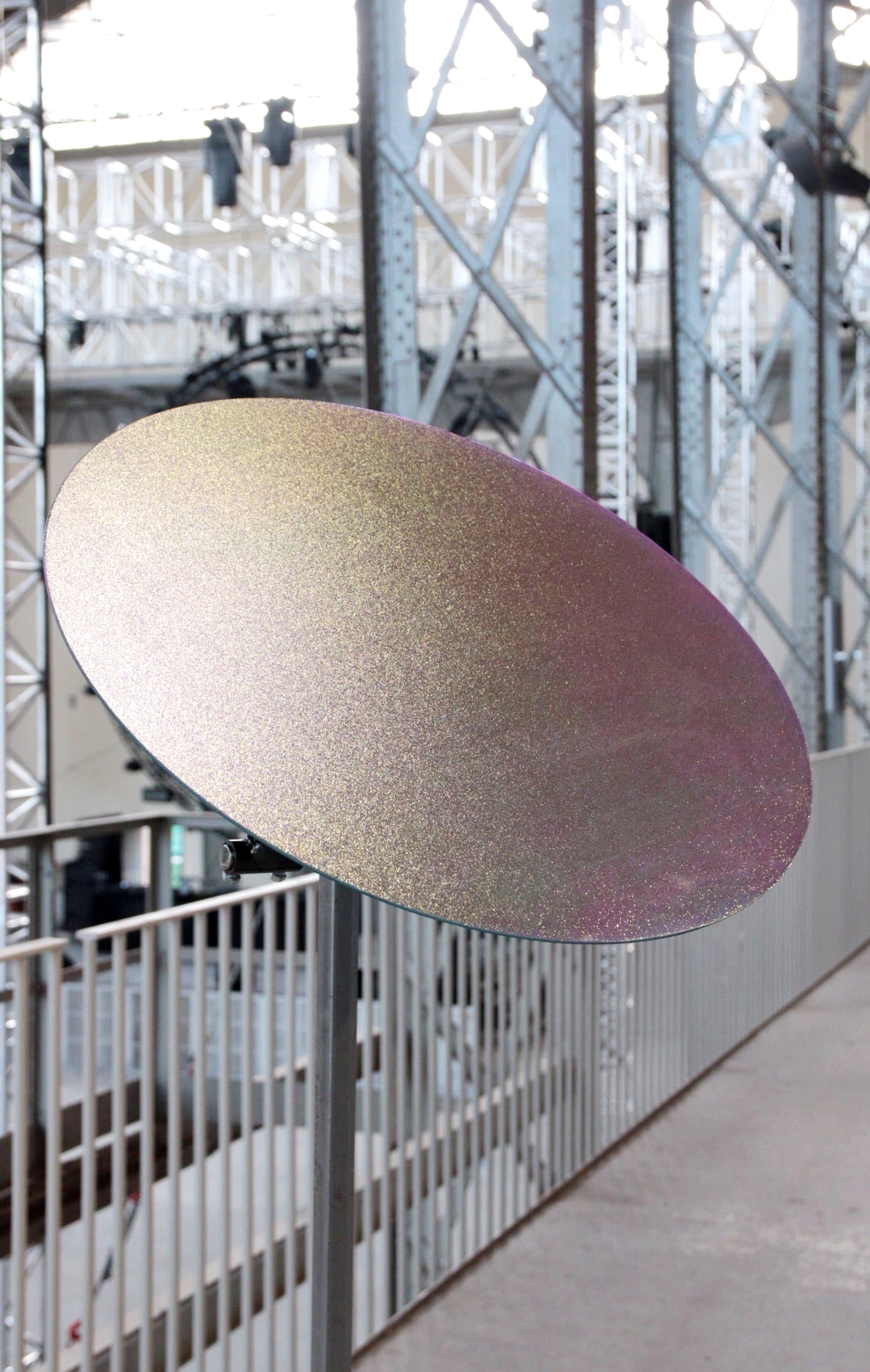

Verre recyclé, filtre dichroique dépoli, acier.

Environ 175 x 90 cm.

En collaboration avec Tanguy Roussel, dans le cadre d’une résidence à l’Hangar Y

avec Art Explora & Artagon.

Recycled glass, roughened dichroic filter, steel.

Approx. 175 x 90 cm.

In collaboration with Tanguy Roussel, in the framework of the residency at Hangar Y

with Art Explora & Artagon.

︎ TLMALP - Salvador Banyo, Karo Kuchar, Tanguy Roussel, Lewis Joly.

—

“We don’t need new worlds. We need mirrors.”

- Solaris, Stanislaw Lem

Lors d’une résidence à l’Hangar Y - le premier hangar à dirigeables au monde - à Meudon (FR) sur le thème de l’exploration, j’ai été intriguée par l’usage du miroir dans le domaine spatial suite à des visites à l’Observatoire de Paris. Ces miroirs contenus dans des télescopes, immenses, étaient tous tournés vers le ciel à l’image de mes propres yeux qui avaient cherché depuis l’enfance quelque chose dans le ciel nocturne que je ne pouvais toujours pas nommer. Pourtant, le thème de l’exploration me poussait toujours à détourner les yeux pour revenir sur Terre : il m’était impossible de séparer ma fascination pour le ciel et ma présence sur cette planète. L’un n’existait pas sans l’autre. Mais qu’avait-il de si important dans le ciel qui valait la peine de faire exploser des satellites dans l’atmosphère, ou encore de les envoyer se noyer dans les profondeurs des océans ? En faisant des recherches sur l’usage du miroir dans le domaine spatial, j’ai été intriguée par le miroir dichroïque, qui avait été utilisé dans les années 50-60 par la NASA comme mécanisme de protection contre les rayonnements de la lumière solaire non filtrée. J’ai tenté de reproduire l’effet du verre dichroïque à l’aide d’un filtre : séparant les couleurs sans les absorber, les couleurs présentes sur le miroir varient selon la lumière ambiante (naturelle ou artificielle) et l’angle d’observation. Ici, le miroir ne cherche pas à aller au-delà de nos capacités visuelles. Il réfléchit les expériences à la fois uniques et multiples qui constituent le fait d’être un être humain sur Terre. Explorer se détourne de discours parfois présentés comme universels et nous invite à remettre en question les manières dont voir et savoir semblent se confondre à une ère où la diffusions d’images est sans précédent.

During a residency at Hangar Y in Meudon (FR) - the world's first airship hangar - on the theme of exploration, I was intrigued by the use of mirrors in the space field following visits to the Paris Observatory. These mirrors contained in telescopes, huge, were all turned towards the sky in the image of my own eyes which had been looking since childhood for something in the night sky that I still could not name. Yet, the theme of exploration always pushed me to look away and return to Earth : it was impossible for me to separate my fascination for the sky from my presence in this planet. One did not exist without the other. What was so important about the sky that it was worth blowing satellites into the atmosphere, or sending them to drown in the depths of the ocean in the name of exploration ? While researching the use of mirrors in the space field, I was intrigued by the dichroic mirror, which had been used in the 50s and 60s by NASA as a mechanism to protect against the radiation of unfiltered sunlight. I tried to reproduce the effect of dichroic glass by using a filter : separating the colors without absorbing them, the colors present on the mirror vary according to the ambient light (natural or artificial) and the angle of observation. Here, the mirror does not seek to go beyond our visual capacities. It reflects on the unique and multiple experiences that make up being a human being on Earth. Explorer turns away from discourses sometimes presented as universal and invites us to question the ways in which seeing and knowing seem to merge in an era where the dissemination of images is unprecedented.